The Aride Timeline

|

851:

Arab manuscript refers to higher islands beyond the Maldives, possibly granitic Seychelles 1503: Thomé Lopes, captain’s clerk of a ship of the fleet of Vasco da Gama reports elevated land: the first recorded sighting of Seychelles. 1609: Crew of English East India Company vessel Ascension record the first landing in Seychelles noting “the other ilands which wee sawe further to the E.N.E. of us”, presumably including Aride. 1768: The members of the Marion-Dufresne expedition give “île Aride” its name, because it appeared to have no running source of water. 1771: Charts drawn up by Du Roslan aboard the Heure du Berger show Aride 1787: Jean-Baptiste Malavois provides first written description of Aride as “…just a pile of rocks covered with some bushes”. 1824: Madame Fauché, a free person, is the first named resident of Aride present together with three unnamed slaves. The proprietor is named as Victorin Morel of La Digue. 1831: Government Agent George Harrison visits Aride and reports a leprosy patient cared for by a slave. 1861: Human population of Aride recorded as two, probably caretakers. 1868: Aride visited by Irish ophthalmic surgeon, botanist and zoologist Edward Perceval Wright, after whom both Wright’s Skink and Wright’s Gardenia are named. 1883: Marianne North, botanical artist, visits Aride, describing it as “that scorching island” and finding just “one big green tree”. 1904: Specimen of Seychelles Magpie-robin collected on Aride by Gustave Thibault confirms presence. Two European Rollers also collected. 1907: Gustave Thibault collects two male and one female Seychelles Paradise-flycatchers on Aride. 1931: Up to 150,000 Sooty Tern eggs are being collected from Aride annually. 1940: Ornithologist Frederick Nicholson Betts visits Aride. Vegetation appears to be managed to encourage Sooty Tern nesting in order to increase the egg harvest. 1954: Sooty Tern egg collection at Aride reaches its peak at 225,000. 1968: Christopher Cadbury spearheads campaign to purchase Cousin Island as a nature reserve, donating most funds for purchase by Society for the Promotion of Nature Reserves (SPNR). 1970: Guy St Jorre, executor to the heirs Chenard (owners of Aride) declares Aride a nature reserve. 1972: Chris Feare and John Procter visit Aride and recommend its designation as a Special Reserve. 1973: Freehold title to Aride Island was purchased by SPNR on 30th January, with funds donated by Christopher Cadbury. 1975: Aride declared legally as a Special Reserve. 1977: First meeting of Aride Management Committee (AMC) chaired by Guy Lionnet. 1979: Aride Island Special Reserve regulations become law. 1981: Adrian Skerrett joins Aride Management Committee as Executive Officer 1984: Biological survey of Aride Island Nature Reserve, Seychelles by Stephen Warman and David Todd published in journal Biological Conservation. 1987: Aride Endowment Fund established with an initial £100,000 donated 50% by Christopher Cadbury and 50% by WWF. 1988: 29 Seychelles Warblers transferred from Cousin Island to Aride. 1990: First meeting of Aride Research Sub-committee (later the Aride Island Scientific Committee). 1989: Aride and Roseate Tern feature on special commemorative stamp. 1990: Seychelles Blue-pigeons recorded at Aride for first time in many decades 1993: Visit to Aride Island by HRH Duchess of Kent. 2001: Island Conservation Society (ICS) is registered on 10th April. 2002: 15 Seychelles Magpie-robins and 64 Seychelles Fodies transferred to Aride. 2003: Edwin Palmer joins the AMC. 2004: Aride is leased to ICS for 3 years. Island Conservation Society UK (ICSUK) is created as a UK Registered Charity to raise funds for Aride. 2007: ICS meets conservation targets set by Royal Society of Wildlife Trusts (RSWT, formerly SPNR). 2008: Transfer of freehold title of Aride from RSWT to ICSUK on 17th October. 2010: RSWT transfers Aride Endowment Fund of £500,000 to ICSUK. 2012: Black Mud Terrapin reintroduced. 2018: Boundaries of Aride Island Special Reserve extended to one kilometre. 2017: Visit by Wavel Ramkalawan and National Assembly Islands Committee. 2018: The book Aride Island, Tread Lightly edited by Tim Sands and Adrian Skerrett is released. 2020: Norman Weber (CEO) and Shane Emilie (Deputy CEO) join ICS and the newly-named Aride Advisory Committee (formerly AMC) |

Human History Of Aride

Judith Skerrett; edited extract from Aride Island, Tread Lightly

Aride first appears on charts by Du Roslan aboard the Heure du Berger between December 1770 and February 1771. The first account, written in 1787 by Jean-Baptiste Malavois, French commandant of Seychelles, described Aride as “…no more than a pile of rocks covered with a few bushes.” Malavois also noted there was no regular source of fresh water and landing was difficult. In a list of islands that in his opinion could support settlers and their families, Aride is not mentioned and was presumably considered unsuitable.

In October 1817 the authorities conceded Curieuse to Mr. Sérèies, who objected to the presence of lepers on the island. In 1818 they were shipped from Curieuse to Aride, which was probably still without a proprietor to protest against the move. Until 1829, when the British government established the new asylum on Curieuse, it is likely that Aride became an unofficial leper colony.

The first proprietor of Aride, Victorine Morel, was a descendant of Maximilien Morel who along with others was deported to Seychelles from the French colony of Réunion in 1798 after an uprising and settled on La Digue. British Government Agent, George Harrison paid a visit of inspection in 1831 and he was surprised to find a leper, a slave by the name of Confiance, still living on Aride and being cared for by one of Mr. Morel’s slaves.

In 1861 the island had a population of just two. However, by 1868, when Dr. Edward Perceval Wright visited Aride, the plateau had been cleared and was producing “good crops of cotton and excellent melons”. He was the first naturalist to explore Aride, and gave his name to Wright’s Skink and Aride’s unique shrub, Wright’s Gardenia.

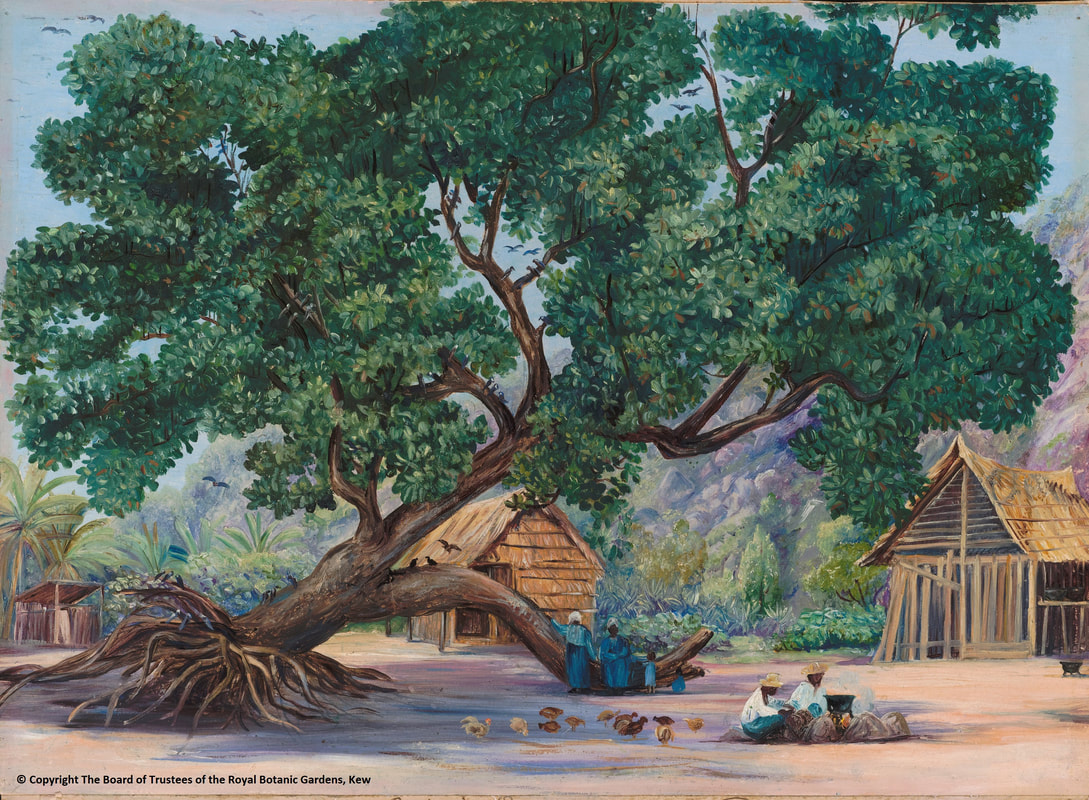

Marianne North, an intrepid Victorian botanical artist, visited in 1883 and described it as “that scorching island”. There was only “one big green tree”, an Indian Almond, under which everyone huddled for shade. However, she also mentions that the island produced bananas, pineapples and other tropical fruits. The painting she did on Aride now hangs in the North Gallery at Kew, London.

Seychelles had entered the age when copra and coconut oil were the islands’ major exports. It is therefore not surprising that by 1940 when the island was visited by the ornithologist Frederick Nicholson Betts, the plateau was “thickly planted with tall old coconut palms with an undergrowth of bananas and fruit trees.” Betts reported that on the hillside, in pockets of soil, maize, beans and water melons were still grown, and a wide range of fruits and vegetables were produced on the plateau.

During Wright’s visit in 1868 the men of his party alone captured and ate nearly two hundred fat young birds in two days. Fifteen years later Marianne North recollected that the island’s proprietor made very good money selling pies filled with seabird meat. By Betts’ time, considerable numbers of Wedge-tailed Shearwaters were being killed, dried and exported to Mahé, along with frigatebirds which were knocked off their roosts with long poles, and noddies which were caught in mid-air using string whips or sticks as the birds hovered around the island boats offshore.

Aride’s egg harvest became the main source of income for its proprietors. In 1931, 200 cases of eggs, with 700-750 eggs per case, were taken from the island. Between 1948 and 1967, an average of 172 cases per year was exported annually with a peak of 312 cases (225,000 eggs) in 1954. Of course many more eggs even than these would have been taken by resident workers and by poachers. After 1975, when approximately 32,000 eggs were gathered, no more eggs were officially collected from Aride.

In 1967, the Chenard family, owners of Aride, decided to sell the island to someone who would protect the wildlife. Christopher Cadbury visited Seychelles around this time. He spearheaded the campaign to purchase first Cousin Island in 1968 and then provided the funds to purchase Aride Island in 1973. Both islands were entrusted to the Royal Society of Wildlife Trusts. In 1975 Aride was given Special Reserve Status by the Seychelles Government. This made the destruction or disturbance of any living thing on the island, or any habitat there, an offence under the law. Since 1984 the island has been scientifically monitored, with an ongoing research programme administered by professional full time scientists. In 2004, Aride was leased to Island Conservation Society. After satisfactory completion of the targets, responsibility for Aride was transferred to ICS. Today, the island’s permanent inhabitants are all engaged solely in the ecological management, conservation, and restoration of the island.